Kenneth Lee, owner of XO Restaurant on Oʻahu, has been preparing to be a restaurateur for most of his life. He opened his restaurant at age 24 with the funds that he earned from investing in the stock market at age 13.

At 17, he opted to study cooking at Kapiʻolani Community College over business at the University of Hawaiʻi, knowing that cooking eventually could turn into a business.

His mom gave him that shot in 2018 when she signed over the lease of her declining Thai restaurant in the foodie neighborhood of Kaimukī to him.

Lee flipped the space from a run-down dive to a sleek, modern gastro-wonderland in just two weeks and got to work.

His prudent yet creative approach to cooking aims to offer high-end dishes without wasting a dime. The result is some of the most interesting food in Honolulu right now.

Beautifying food scraps, pushing the boundaries of creativity and maximizing efficiency enable Lee to produce fine dining on a tight budget at XO.

Lee, a protégé of Anthony Rush and Chris Kajioka of Honolulu’s acclaimed Senia, named his venture after the Chinese XO sauce to imply opulence and prestige while paying homage to his Chinese heritage.

XO sauce, first developed in Hong Kong, comprises extravagant ingredients and requires an adept hand to produce. It was named after XO cognac, an aging classification given to cognacs, to denote its high quality.

Lee shows his skills – both at cooking and business – by manipulating high-end ingredients such as foie gras and wagyu beef to fit his budget. He and his right-hand man, chef de cuisine Harrison Ines, have a knack for transforming food scraps into delicious and thought-provoking dishes.

For example, they took the silver skin from wagyu beef – a scrap often discarded by most chefs – cured it with salt and sugar, fried it and minced it to create an elegant condiment that offers the essence of wagyu beef.

Another lavish victory created from economic necessity is their foie gras dish. A lobe from Hudson Valley Foie Gras costs about $90. In order to afford this fine-dining staple, Lee purchases foie gras scraps from a specialty purveyor for $24.41 a pound instead and, with the help of Ines, elevates it into a dish that he can charge high dollar for.

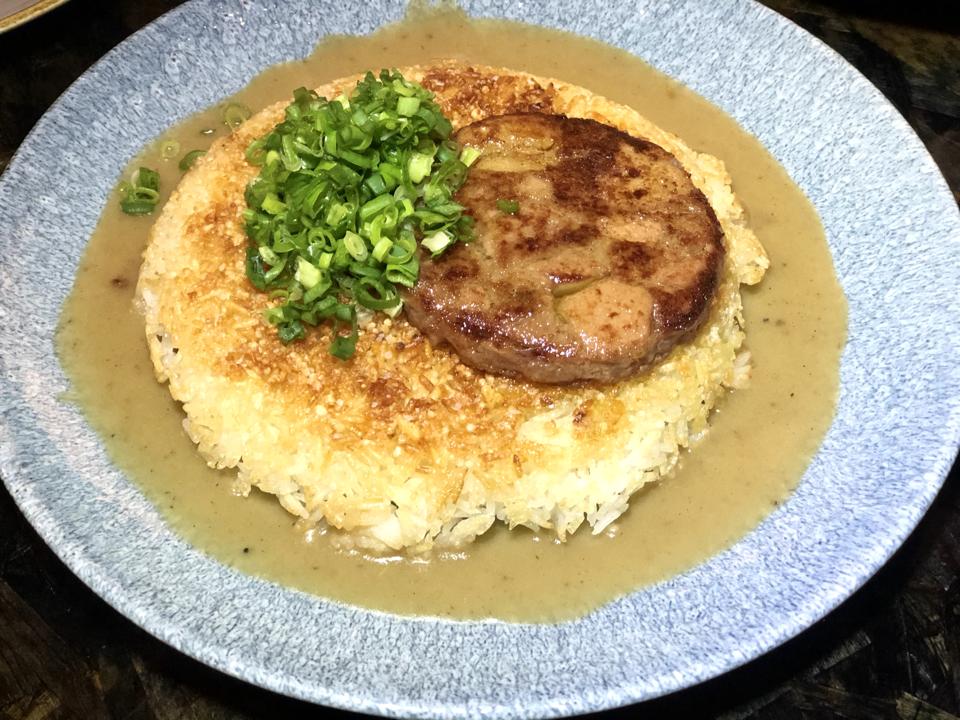

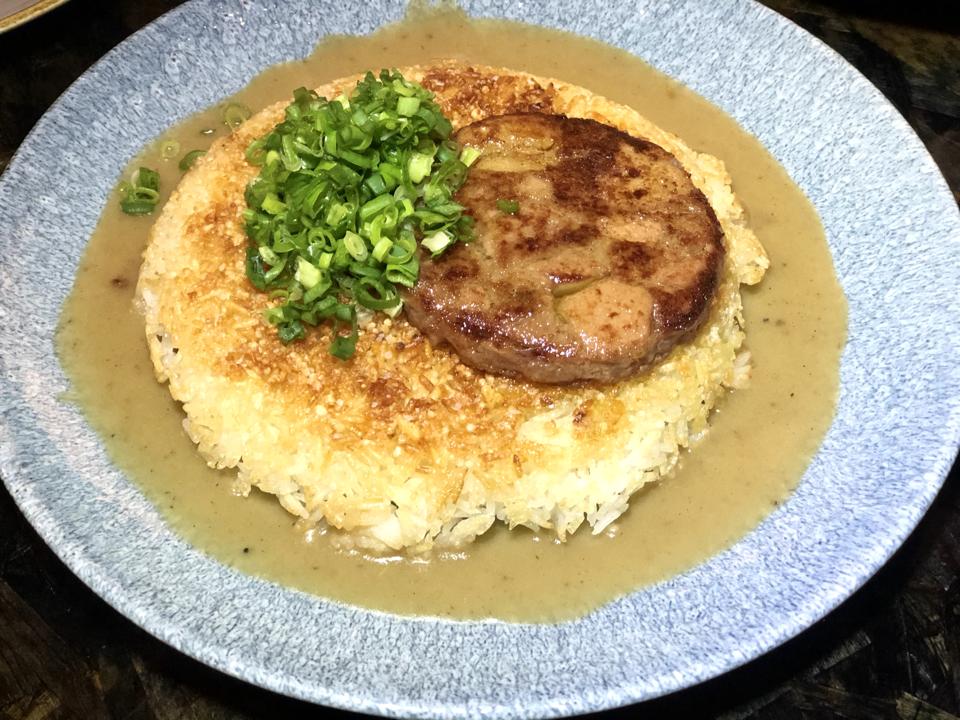

Ines chose a technique that binds meat together using transglutaminase – an ingredient chefs have nicknamed “meat glue” – to create a beautiful roulade that the duo slices and sears like a slab of bologna. Think sophisticated scrapple – a Pennsylvania breakfast staple made of compressed, pan-fried pork scraps. They serve the sumptuous slab over a perfect disc of Chinese crispy rice with a gravy made from the foie gras pan drippings drizzled around the perimeter of the plate to drag each bite through.

Their avant-garde twists on time-honored recipes wow you while keeping you in your comfort zone.

Lee’s creativity comes from understanding cooking and desiring to preserve as much as possible to avoid throwing spoiled food and, therefore, money away.

“It’s kind of grim, but most of my philosophy of everything is based on death and the fear of it,” he says.

Take the restaurant’s scotch bonnet egg, for example. A deep-fried, soft-boiled egg coated with sausage and panko breadcrumbs. A classic bar snack – except for the tubs of brine that the eggs soak in on the bar.

Lee uses a modern approach to an ancient Chinese preservation technique to create century-old eggs – preserved eggs that contain a dark-green, creamy yolk and a gelatinous, brown white.

The familiar element of this dish arrives in the delicious spicy sausage enveloping the egg that Lee modeled after his favorite pizza topping: Pizza Hut’s Italian sausage. In his experience, diners think food tastes off if it strays too far from what they are used to.

“Subconsciously in your head, it tastes right when it tastes like what you know,” he says.

Lee’s clever and thrifty dishes take guests on an interesting journey every visit to XO. He carefully plans every ingredient on the plate and every step to combine them. He also changes the menu every three months.

“I do a lot of thinking,” Lee reflects.

His inquisitiveness and inventiveness set him apart during his culinary training days.

“The biggest question for me was, ‘Why?’ he says. “… People teaching me didn’t like me because I was always like, ‘Why are we doing it like this?’ I wasn’t asking to be a brat. I was just asking, ‘Why do we do it like this?’”

The cost of running a restaurant is high. At some point, either the labor or the ingredients typically bear the brunt. Lee focuses on preserving both.

“When we first opened, I based the menu mostly around necessity and survival because it was just two of us in the kitchen and then we have to do everything ourselves,” he says. “So, when we first opened, the menu was based on, like, things lasting a long time so there’s no waste because we weren’t sure if we were actually going to sell it or if we were going to end up throwing money away.”

Now Lee applies this efficiency to taking care of his staff – one of his top priorities. He strives to save everyone time in order to pay his team well and to avoid burning out cooks.

“I’d rather hire a couple people and make them very efficient,” he says. “Like, if two people can do three people’s job, you can pay three people’s worth of money to two people.”

During an era in which cooks are notoriously hard to find – restaurants all over the country seem to be in a drought – XO is a magnet for them.

“I don’t advertise, like, ‘Hey, I pay a lot of money!’” Lee says. “… I guess just word of mouth just based on the food alone, that’s how they end up here, and then they find out that, ‘Oh, the working environment is actually good!’ Like, nobody is getting screamed at, nobody is pulling hairs out because they can’t get their prep list done, and everyone works easy hours for a kitchen, and the food comes out nice in the end, which is, like, perfect! It’s sustainable.”

Lee spends a large portion of his time in the kitchen finding ways to produce his food more efficiently. For example, for his potato gnocchi, he eliminates the step of rolling, shaping, blanching, cooling, and warming the dumplings up again later by refrigerating the dough and scooping it into patties to order. His crew deep-fries the scoops and serves them with all of the fixings of a loaded baked potato. The addition of mochi flour to the dough creates a pleasantly chewy and crispy french-fry-like treat.

Ultimately, what you are paying for when you come to XO Restaurant is Lee’s brain and the fruits of years of trial and error and an endless quest for answers.

“It’s just cooking,” he says humbly. “We just do what we do, and, whatever direction it stems off into, that’s where it lands.”

Source: Forbes